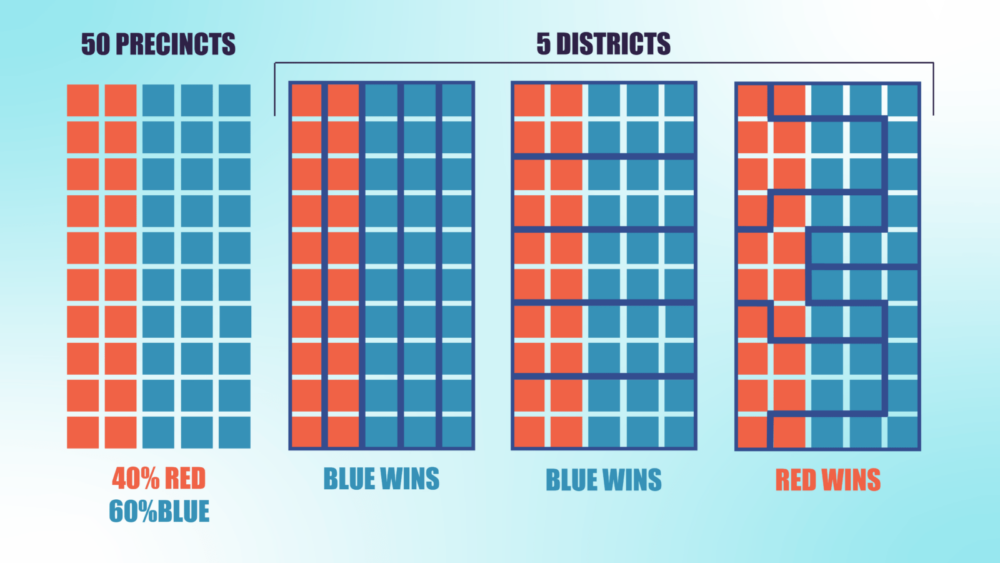

Gerrymandering is the act of favoring one political group over another through the manipulation of redistricting maps. Each state is broken into districts for the House of Representatives, which is proportioned based on state populations (unlike the Senate, for which each state gets two Senators). By ensuring one political party’s voting bloc is more effectively concentrated in specific districts, the party in power can ensure they remain in power, even if they actually have fewer voters than the other party.

If that sounds like a recipe for disaster, welcome to the party. Most Americans oppose partisan gerrymandering, while only a small sliver outright supports it—a substantial minority simply don’t understand it.

When it comes to the defense of gerrymandering, the most coherent argument tends to be, “Well, both parties do it.” That’s true. Republicans do it in states where they control the legislature, and Democrats do it in states where they do. So, fair’s fair, right? Everyone does it, let’s move on.

Absolutely not. Just because both parties take advantage of this system doesn’t make it a good or fair system. Furthermore, in recent years, Republicans have benefited from gerrymandering far more than Democrats (though Dems have been fighting back).

Gerrymandering is such an obviously corrupt system that versions of it have been declared outright unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Pathetically, the Supreme Court has generally punted on gerrymandering cases, arguing that these are political issues that must be decided by each state’s legislature. But the Court did strike down gerrymandering by race, declaring it unconstitutional. Frustratingly, there are workarounds.

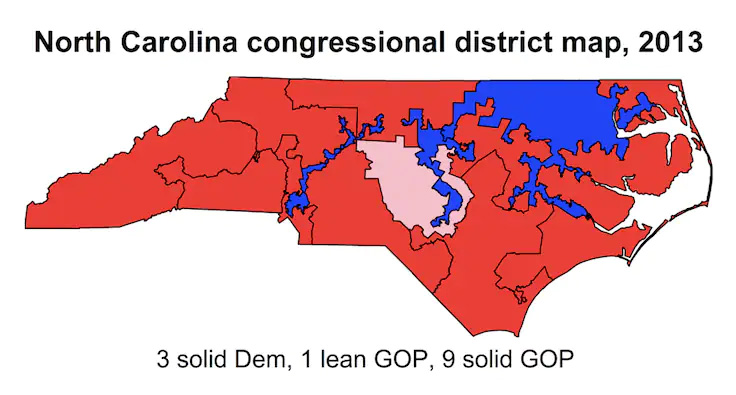

In fact, the Republicans have elevated gerrymandering to a racist art. In 2020, we learned that long-time GOP political strategist Thomas Hofeller, now deceased, had been one of the chief architects of the party’s gerrymandering efforts, having helped radically shift districts across the country with the use of extensive racial data. Under the guise of partisan redistricting, the GOP has been engaged in racial gerrymandering for decades.

Even when lower courts have ruled that a gerrymandered map was unconstitutional, the Supreme Court has sometimes reversed the decision, as it recently did with Merrill v. Milligan. The Alabama Supreme Court found the state’s new redistricting map disadvantaged Black voters, so they tossed it out. But the US Supreme Court stepped in and has allowed that map to stand for the 2022 election.

A necessary evil?

The official stance of the Supreme Court is that partisan actors are the best people to address partisan issues. Which strikes me as faulty logic, but if that’s what the highest court in the land believes, then only state legislatures can fix gerrymandering. How likely are they to do that? Well, consider how this all works.

Once a decade, at least, all 50 states must redraw the boundaries of their political districts following the Constitutionally mandated national census. Redistricting is not only necessary, it’s good. Over a decade, populations change dramatically, both in terms of size and location. By regularly redrawing the districts, states theoretically ensure its residents are truly represented.

Sadly, those in charge of redistricting are the very ones whose jobs will disappear if their voting base has dwindled or moved away. Hence gerrymandering exists to ensure those in power stay in power.

Maybe the courts can bar racial discrimination in gerrymandering – though recent Supreme Court decisions have shown the institution isn’t interested in protecting the voting rights of minorities – but political gerrymandering seems here to stay. Just a necessary evil, perhaps?

It shouldn’t have to be.

While redistricting is vital and required by the Constitution, there’s nothing that says districts need to be carved up to look like the abstract art. Austin, Texas is a left-leaning oasis in the state, and yet its large liberal voting bloc is all but neutered by gerrymandering. Meanwhile, despite the voting base of Houston increasingly shifting toward the Democratic Party in recent decades, it’s comfortably held by Republican Representative Dan Crenshaw because his district looks like a tapeworm painted by Picasso.

Maybe the Democrats will one day give the Republican gerrymandering machine a run for its money, but that’s not a better outcome. We shouldn’t be hoping for more bipartisan political hackery. We should be creating a system that truly represents the ideal of “one person, one vote.”

Fixing gerrymandering

The solution to all of this couldn’t be simpler: base redistricting on county lines in every state, and if states don’t want to do it, then deny them federal funds until they do.

It would be fairly simple to implement, since counties are pre-existing state divisions, and for national elections, states already collect their voting tallies at the county level. In states like Washington where the population of large cities dwarfs those of smaller counties, bigger counties can be divided in half or thirds as needed, and smaller counties could be grouped in geographical sectors.

President Biden could accomplish this by Executive Order, or it could be passed by Congress at the Federal level. Even if Republicans control the Senate and/or House, they might be persuaded to take up the legislation. After all, it’s not unthinkable that Democrats could gain control of a few important swing states, like Wisconsin or Michigan, and gerrymander Republicans completely out of power.

Another option would be to hope that state governments would choose to outlaw it, as has occurred to some degree in Washington state, where a five-member committee composed of two Republicans, two Democrats, and a nonvoting member redraw election boundaries conjointly once per decade, following the Census. Unfortunately, more conservative states are unlikely to go along with it willingly.

Thus, we need to start from the Federal level, building upon more moderate, piecemeal successes in states like Washington, which have already set a precedent for how this could occur at the national level.

Whichever route we take, the time to act is now.